Fuzzing Smart Contracts Using Input Prediction

In the previous post, we discussed several approaches for automatically finding vulnerabilities in smart contracts and we introduced Harvey: a fuzzer for Ethereum smart contracts being developed by Consensys Diligence: Smart contract auditing, in collaboration with Maria Christakis from MPI-SWS and that will be one of the tools powering our MythX analysis platform.

Grey-box fuzzers are able to achieve high code coverage even for complex code without using more expensive techniques, such as automated SMT solvers, to reason about the program. However, for many programs it can still pay off to perform some lightweight reasoning about the code to increase code coverage more quickly. In this post, we will present a novel input prediction technique for grey-box fuzzers.

Motivating Example

Let’s go back to the smart contract from the previous post (written in the Solidity programming language) to illustrate a limitation in state-of-the-art grey-box fuzzers.

contract Foo {

function Bar(int256 a, int256 b, int256 c) returns (int256) {

int256 d = b + c;

if (d < 1) {

if (b < 3) {

return 1;

}

if (a == 42) {

assert(false);

return 2;

}

return 3;

} else {

if (c < 42) {

return 4;

}

return 5;

}

}

}

Most grey-box fuzzers will take a long time to detect the assertion violation since inputs are fuzzed randomly; the chance of picking a to be 42 is tiny. For instance, AFL, a state-of-the-art grey-box fuzzer, was not able to generate a test that violates the assertion within 12 hours. While there are a number of heuristics that fuzzers can employ (e.g., picking new inputs from the constants in the program), Harvey also integrates a more systematic approach that we will present below.

Predicting New Inputs

Let’s assume that Harvey generated an input I with a==0, b==3, and c==-3; it explores the path that returns 3 (on Line 12). We would like to predict a new input F, that will explore the then-branch of the last conditional along the execution of input I (on Line 8).

As discussed in the previous post, one could use white-box fuzzers that symbolically execute the desired path and use SMT/SAT solvers to create new test cases. However, this can be expensive and one might prefer a more lightweight approach that builds on the grey-box fuzzing algorithm introduced in the previous post.

Let’s assume Harvey generates a new input J by changing parameter a of input I to 7. Even though this new input still executes the same path, we can extract information that will allow us to predict an input that explores the desired branch.

All we need to do is measure for both inputs how far we are from “flipping” that branch (i.e., by negating the branch condition). For input I this distance is 42 since we would flip the branch if we were to increase a by 42. Similarly, for input J the distance is 35. We record these distances while running inputs which does not incur much overhead since grey-box fuzzers already perform some lightweight instrumentation to record a path identifier during execution. The distance for a given branch is computed automatically during the execution of the EVM bytecode based on the type of comparison operator that is used (e.g., == and <=), and the concrete arguments to the operator (e.g., 7 and 42). In other words, we use a simple mathematical formula that determines the distance for each operator and its arguments. For instance, the distance formula for flipping to the then-branch is absoluteValue(42-a), whereas it would be 42 - a+1 if the condition of the desired branch was 42 < a.

By simply comparing the distance of the given branch for both inputs, we already learn something useful: the change in distance confirms that we are on the right track by fuzzing a. Essentially, we learn that a taints the condition of the desired branch without even running any expensive taint analysis.

Now, to actually predict the new input, we can think of the distance as an unknown (but computable) mathematical function f(x) where x is an input parameter that was changed. In our example, parameter a was changed and we happen to know two concrete values of our distance function f: f(0)==42 and f(7)==35. The key insight is that we are now able to phrase the problem of finding the desired input as the problem of finding a value x’ such that f(x')==0.

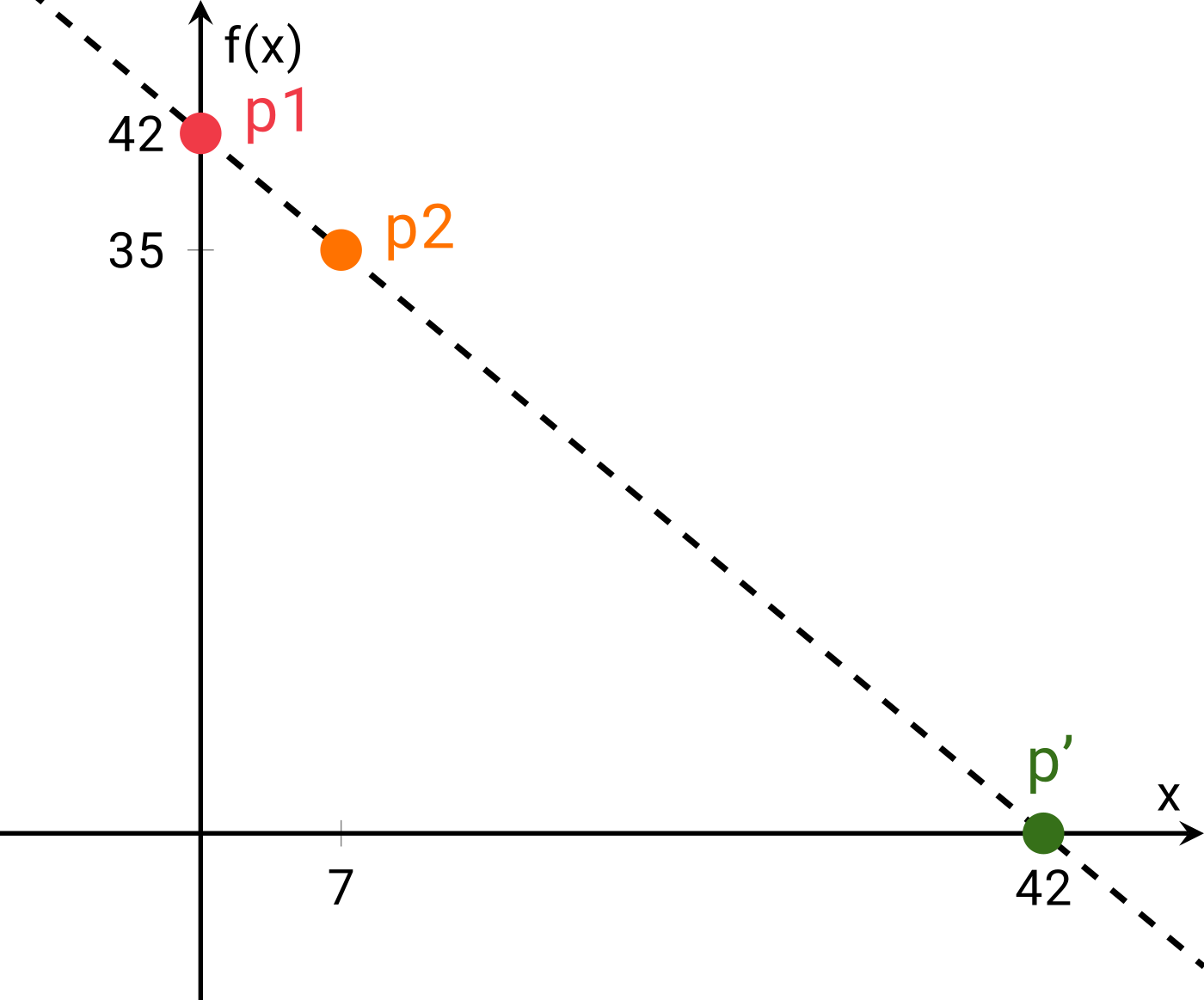

This problem has been studied extensively and there are many different methods, such as Newton’s method. In Harvey, we use an approach that is known as the Secant method. It works by essentially drawing a line through the two known points of the function, p1 at (0,42) and p2 at (7,35), and determining the x-coordinate of point p’ where the line intersects with the x-axis, i.e., (42,0). Harvey then uses this information to derive a new input with a==42 that will be tried next.

Known points p1 and p2 let us derive point p’ whose x-coordinate corresponds to the new predicted input.

Et voilà! By running the input we confirm that it indeed explores the desired branch. If we were less lucky, we could apply the same approach iteratively, for instance, if the branch condition was a*a*a==27. However, in practice, we found that this is almost never necessary.

This simple but elegant technique typically allows Harvey to find vulnerabilities orders-of-magnitude faster. For our example, it allows Harvey to achieve full coverage within less than a second whereas it takes Harvey roughly 14 seconds without input prediction. See our paper for more details (including an extensive evaluation on real-world smart contracts).

In the next post of this series, we will look at how Harvey detects vulnerabilities that can only be triggered if an attacker issues multiple transactions. Stay tuned!

Thanks to Maria Christakis, Joran Honig, John Mardlin (aka Maurelian), and Bernhard Mueller for feedback on drafts of this article.

Thinking about smart contract security? We can provide training, ongoing advice, and smart contract auditing. Contact us.